Modern art tends to be shit, but this piece that I stumbled upon scratched an itch.

The art seems simple. Four humans dressed in prison clothes. They face a cage and are postured towards it. The prisoners are uncaged, free, liberated; yet it seems like they long for the cage. Huh? Why would the prisoners want to be caged?

Perhaps they aren’t actually free. If they were free, then they wouldn’t be facing the cage or walking towards it. They would be doing anything but going towards oppression (assuming freedom is intrinsically desireable).

If that is true, then like the statues, the horrifying conclusion is that we are also imprisoned. We are the prisoners. But we are free, right?

I feel free. I had the freedom to do what I want – I chose to go out that day to Parkview with my friend, and I could’ve just as easily flaked on her (sorry J!).

The artist tells us that the problem is the very state of our freedom. Paradoxically, freedom cages us. True liberation might very well lie in the boxes we desperately wish to think and break out of.

I think that the artist1 does have a point. Let me elaborate.

Choices and psychology

The paradox of choice is a relatively well known concept, coined by psychologist Barry Schwartz. Essentially, to be free is to have choices and the ability to act on them. However, choices do not scale with happiness.

When we have too many options, we have incredible freedom since more actions are unlocked for us, but this burdens us. Prof Barry talks about 3 ways this happens.

First, analysis paralysis. Despite having so many possible actions, we just don’t do anything2. Are we really free if choice overload makes us shut down3? No.

Second, we are less happy with the choice we make. The perceived opportunity costs dampens satisfaction of our choices. Are we really free if we are preoccupied with the thought of ‘what if’? No.

Third, we expect too much. Surely one of the many choices available to us must be perfect, and we fantisize about the possible goodness of this hypothetical choice. Ultimately, we are disappointed when the heaven we have built up in our minds comes crashing down once the action’s outcome is realised. Philospher Slavoj Zizek4, in The Pervert’s Guide to Cinema succinctly descibes this gap between reality and fantasy:

We have a perfect name for fantasy realized. It’s called nightmare.

A perspective from math and computing

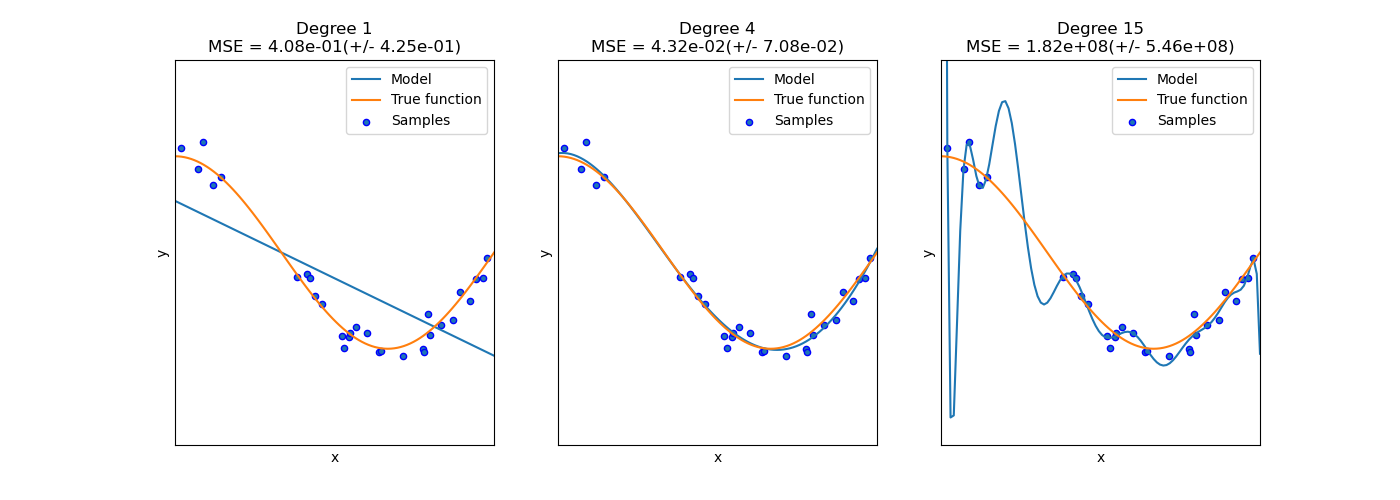

Clearly, having too much freedom leads to suboptimal outcomes and restricts us. Surprisingly, this is not a purely human thing and is also observable in more concrete sciences5. I will use a simple polynomial model to illustrate.

If “degrees of freedom” mean “number of actions” a model can take6, the more actions we give it, the more likely it is to overfit.

Being able to form ‘perfect’ models (least constrained) at the start usually means a shit model. When more unseen data points are added, the model will fail to generalize well (actually accurately predict the true pattern). Paradoxically, the more freedom we give the model, the less able it is to focus on the bigger picture.

The same can be applied to the way we (humans) make decisions too. I assume we are somewhat rational and would like to make the best decisions. So, when presented with so many choices and possible actions, we do all the internal calculations and get caught up in the cobweb of decisions. We fail to see the bigger picture (sir this is a Wendy’s, just choose what to eat dammit!). And just like training a super unconstrained model, it takes a long time for the human to finish compiling making a decision.

This whole spiel implies that the more constrained (less free) things are, the better outcomes are. This brings me to classical artificial intelligence.

Classical Artificial Intelligence and Freedom

I love classical artificial intelligence. It gives an interesting view on solving problems. Most (actually, all) classical problems are search problems. We are searching for the best way to traverse a maze. Searching for the best chess move. Searching for the meaning of life, the universe and everything7.

Daily decision making can just as easily be modelled as a search problem. Searching for the best meal. Searching for the best pair of jeans, etc.

Classical AI talks about ‘good-enough’ solutions. And good enough is, well, enough. Although many classical AI problems have perfect solutions (like the shortest path in a maze), many don’t as well (chess). This reframing is what is important to resolve the problem of choices. So how do we search in classical a.i.? Three important elements: metrics, constraints, heuristics.

We need metric(s) to evaluate how good a decision is. If the metric we choose is not well defined, then it is hard to make a concerete decision on what to do. IRL, this may be the price of any item you wish to purchase.

Constraints are additional rules to filter out the noise. For example, in a prime number searching algorithm, we may add a constraint that we do not consider even numbers. This reduces alot of noise, since we do not need to consider every other number. IRL, this may be the color of a handbag you want to buy (definitely not red).

Heuristics are rules of thumb that guide you to the best, good-enough solution. In a maze searching problem, this could be the distance from where one is to the endpoint. IRL, this could be that Spanish cuisine is always a banger when choosing what to eat.

These three elements should be intuitive to apply to real life decisions. It shouldn’t be that difficult to come up with some for any decision making problem in your life. And just like that you can borrow from classical AI to use in your real life.

Constraints will set you free

Freedom is important. It is always better to have more freedom and more choices than not. The distinction here, is how we equip ourselves to be able to seperate the chaff from the good stuff of life.

But this does not mean we aren’t free. We can always adjust these constraints as life requires. What matters is not running into a death loop and not engaging with life fully.

Life shouldn’t be about chasing the perfect and fantasies. Perhaps just being able to make informed, good-enough8 decisions is optimal compared to being chained to the fantasy of perfection. This is definitely what the artist must have meant /s. By caging ourselves with informed constraints, we transform from the orange painted prisoner into a caged bird that is free – truly liberated from the tyranny of freedom and choices.

Constraints shall set me free. Now to decide what to eat for dinner…

This may not be the intended message of the artist tho but I wanted to write an essay about my interpretation so there’s that… ↩︎

Prof gave an excellent example from Vanguard (mutual fund company). Employees are given choices of investment funds to invest in, and the employer will match them. It is found that for every 10 funds offered, the rate of participation went down 2%. ↩︎

For the CS nerds, imagine a fork bomb:

:(){ :|:& };:↩︎Caveat: I run the risk of grossly misrepresenting Zizek here, since his conceptual definition of ‘fantasy’ is rooted in psychoanalysis. So take my link with a handful of salt. ↩︎

I am not a statistics or math nerd. So this link might not be 100% watertight and is most definitely a conceptual leap. :haha: ↩︎

If this is unclear, consider each parameter in the model (x0, x1, x2…) as actions. A 2-degree can only have 2 actions, adjust x1 or x2. An N-degree model can have N actions to play with. ↩︎

Trivially, 42. ↩︎

In classical AI, good-enough is usually best. Perhaps the same can be said for life. ↩︎